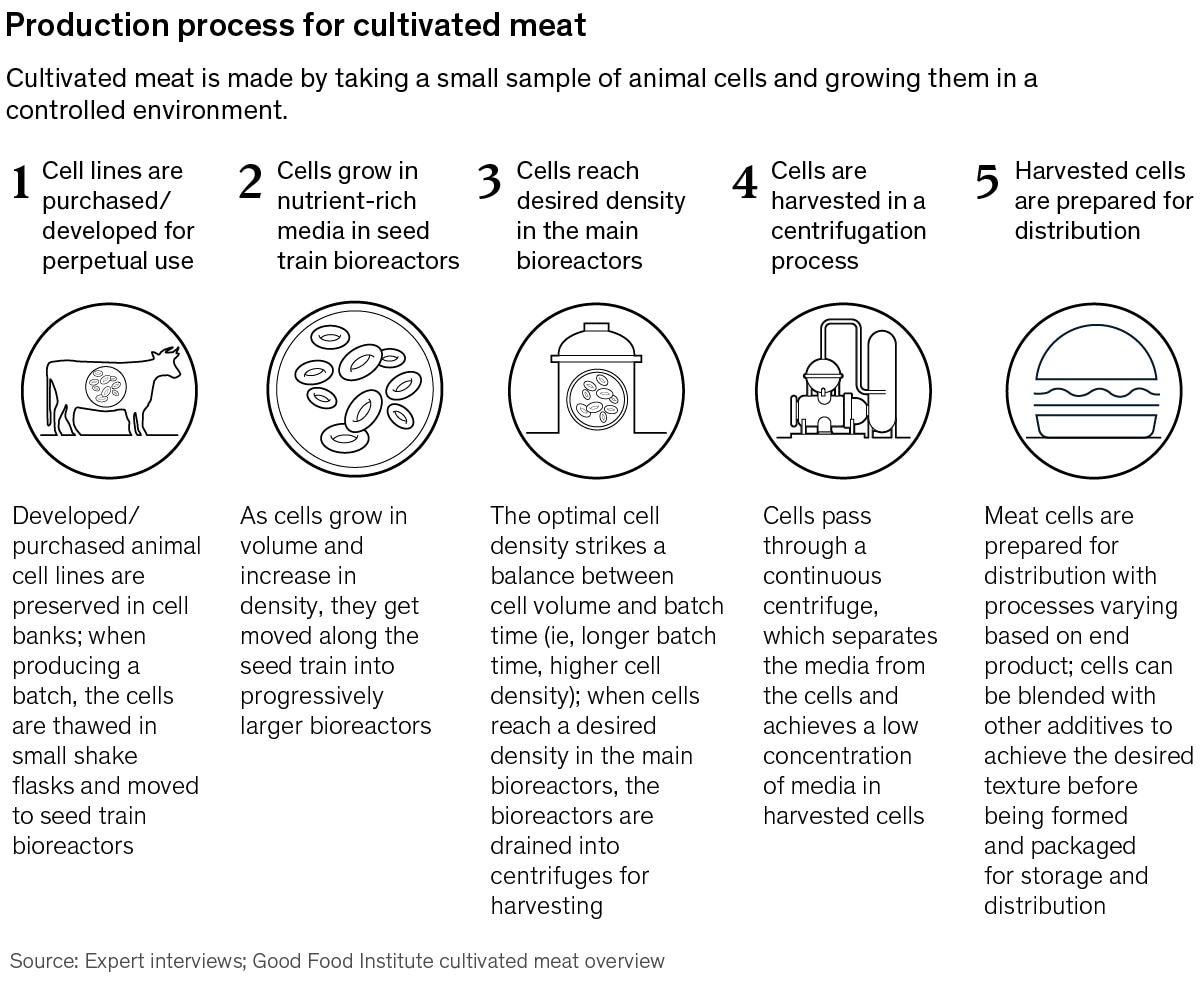

| This week, we talk to some of the pioneers behind cultivated meat about the product’s potential health and environmental benefits. Plus, two McKinsey experts discuss how companies can retain employees, and ideas for inclusive growth as New York City bounces back. | | | | | Setting the table. The feasting season is upon us, and that often means meat—from Thanksgiving turkey in the United States to Christmas goose to roast duck for the Lunar New Year. Yet in their day-to-day lives, many people are cutting back on meat, citing concerns about the sustainability, health, or ethics of growing animals for food. That’s helped create an opening for some promising alternatives. | | Hardly a nothingburger. For some time now, plant-based “meat” producers, such as Impossible Foods, have been able to cut through skepticism and ramp up into viable businesses that are in serious expansion mode. The next wave is a return to meat, with a twist. | | By any other name. Whether it’s called cultivated, cultured, lab-grown, or “slaughter-free” meat, it is still meat—but grown outside an actual, say, chicken, pig, or cow. Pioneers in cultured meat start with animal cells and then grow them in nutrient-rich bioreactors. After several weeks, the cells are ready to be formed into steaks, cutlets, or sausages. Then comes the hard part. The goal is to replicate the taste, texture, smell, nutritional composition, and appearance of conventional meat. But the industry must assuage potential concerns—such as consumer acceptance, and health and safety risks—while delivering delicious novel foods at the right price. |  | | Selling points. The potential benefits of cultured meats include health, nutrition, and sustainability. The meat can be grown in a sterile environment, helping to prevent foodborne illnesses without antibiotics, Didier Toubia (the cofounder and CEO of cultivated-meat start-up Aleph Farms) told McKinsey. Instead of feeding an animal for months or even years “and then eating only 40 percent of it, we can reduce the amount of land and water needed to create the same amount of meat by 92 to 98 percent,” said Toubia. Oh, and cultivated meat produces the same enzymatic reactions that occur during cooking, he said—like that coveted Maillard reaction. | | Ramping up. The challenge is how to increase production to reduce costs enough so that cultivated meat will be economically viable for consumers. Josh Tetrick, the cofounder and CEO of cultivated-meat company Eat Just, told McKinsey that his goal is to beat the price of producing conventional animal protein, such as chicken. That will take a big investment in the bioreactors where the cells are grown. “Part of the challenge is there’s not a company that we can go to and say, ‘We would like to get one of your 100,000-liter bioreactors.’ They have to be built from scratch. So we can’t just plug in; we have to build it. That takes capital. It takes time,” said Tetrick. | | |  | | | | PODCAST | | ‘We are all humans in a crazy environment’ | | So notes Bill Schaninger, who joined Aaron De Smet, a fellow senior partner and expert in talent and organizational health, to discuss what’s behind the “Great Attrition”—the ongoing trend of people quitting their jobs—and how companies should think about this employee moment. “Leaders might want to reconsider the actual nature of their relationship with employees. They’re not servants. They’re not there to do your whim. They’re there because they have a purpose,” Schaninger said in a recent episode of The McKinsey Podcast. “We’re not saying it’s not hierarchical for work allocation, but it certainly is egalitarian when it comes to being human.” | | |  | | MORE ON MCKINSEY.COM | | Twelve insights for an inclusive economic recovery for New York City | More than a year after the city went into lockdown, the most populated metropolis in the United States, and one of its greatest engines for economic growth, is slowly recovering. We look at the remaining challenges and how they can be addressed. | | Digitally native brands: Born digital, but ready to take on the world | Such DNBs are growing, on average, at triple the rate of overall e-commerce. By applying the right criteria, investors can identify brands with the potential to outperform. Here are four critical factors to consider. | | How CEOs can scale AI like a tech native | Embedding AI across an enterprise to tap the technology’s full business value requires shifting from bespoke builds to an industrialized AI factory. Machine learning operations can help, but the CEO must facilitate the process. | | | | | | | WHAT I’VE LEARNED ABOUT CAREERS | | Ryan Davies | | Ryan Davies, a senior partner in Washington, DC, helps clients execute large-scale transformations to improve their organizational performance and health. A father of four, he enjoys running, cooking, and trying to get enough sleep. | | | | | | I often get asked what the most important factor is for a strong career trajectory. I don’t think there’s one right answer—even within, let alone outside of, management consulting. Having a growth mindset and a willingness to view one’s own success as a function of making others successful are both high on the list. But often these days, I’m moved to respond by describing three related qualities: intellectual curiosity, intellectual honesty, and intellectual humility. | | Intellectual curiosity is essential to our ability to think outside the box, understand complex issues, and get energy from the problem solving that’s at the core of the work we do. Most of us are intellectually curious, but sometimes the expression of that strength can be inhibited, often by insecurity. | | Intellectual honesty is a distinct element of effective problem solving: the responsibility to hold ourselves to the highest standard and exert every effort to make sure we are not biased in our insights and recommendations. I feel lucky to have grown up absorbing this ethos from scientists, ranging from my father’s role modeling to the writings of Richard Feynman. We’d probably all say we are intellectually honest, but it’s another matter to stand up for what we believe when others—especially in positions of power and influence—disagree. | | Intellectual humility is pivotal as well. Many people—myself included—see being smart as a core part of their identity, self-worth, and self-confidence. But acting like you are smarter than others, whether or not that’s objectively true, can impede one’s ability to build trust, foster collaboration, and even get to the best answer, despite good intentions. | | I started my career with plenty of intellectual confidence and pride—and, in retrospect, my biggest early professional struggles stemmed from this. I still vividly remember walking into my one-year review, expecting to hear how great I was, and instead being told, “You are great at some things, but also have major development areas to address.” | | I made progress over the next few years, but in some ways it was superficial. I became attuned to the different things I said or did that conveyed a sense of intellectual superiority, however subtly, and I got better at not doing that. I became a genuinely better listener, more conscious of my tendency to focus on “reloading” in my own mind over what another person was saying. I still made periodic mistakes along those lines, but not to a level that held back my overall growth. | | But, to be brutally honest, it’s one thing to avoid acting like you think you are smart in a way that irritates others, and another to truly, fully value their input. Some years later, a classroom exercise memorably opened my eyes to this fact. [Harvard Business School] professor Amy Edmondson, known for her research on “teaming,” was conducting a game for five teams to climb a mountain together in a step-based scenario. | | My competitive juices were flowing, and I took charge and guided all of my team’s deliberations closely from the start. I felt pretty good about how it all went. And then the scores came out, and we were second to last. My directive approach had failed to surface multiple important pieces of information at multiple different steps, leading to multiple subpar decisions. What the heck?! | | As we debriefed the exercise, I realized that no matter how knowledgeable you are, your best individual answer will never be better than the answer that combines what you know with what others have to add. I’ve found that to be a powerful mantra ever since: more perspectives lead to better insights and better decisions. | | — Edited by Barbara Tierney | | | Share this What I’ve Learned |  |  |  | | | | | | BACKTALK | | Have feedback or other ideas? We’d love to hear from you. | |  | | | Did you enjoy this newsletter? Forward it to colleagues and friends so they can subscribe too.

Was this issue forwarded to you? Sign up for it and sample our 40+ other free email subscriptions here. | | | This email contains information about McKinsey’s research, insights, services, or events. By opening our emails or clicking on links, you agree to our use of cookies and web tracking technology. For more information on how we use and protect your information, please review our privacy policy. | | You received this email because you subscribed to The Shortlist newsletter. | | | | Copyright © 2021 | McKinsey & Company, 3 World Trade Center, 175 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10007 | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment