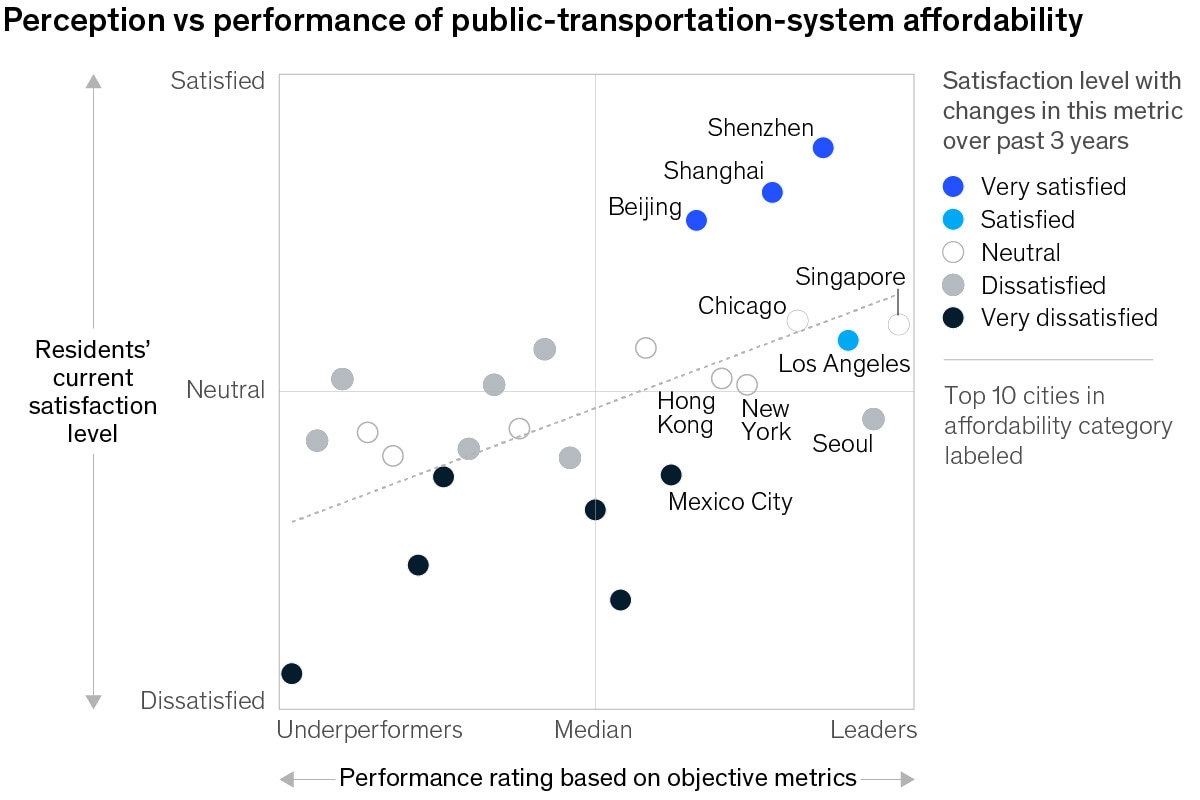

| This week, the role that historically Black colleges and universities have played in economic mobility; why practicing at learning makes perfect; and Parag Khanna takes on the question of how humanity will distribute itself in the coming decades amid the swirl of global risks and challenges. | | | | | The very first higher-education institution for Black Americans, the African Institute, was established in 1837. At the time of its founding, the vast majority of US colleges banned Black students. And even after the passage of civil-rights legislation nearly a century after the Civil War ended, Black students weren’t welcome at many public and private institutions. The African Institute (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania) and the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that followed filled the important need of higher education of and advancement for students of color. | | Today, around 300,000 students on average attend the more than 100 higher-education institutions that identify as HBCUs. Although HBCUs represent just 3 percent of all higher-ed institutions in the US, they are highly effective at serving the populations they were originally established to serve, conveying 17 percent of all bachelor’s degrees and 24 percent of all STEM-related bachelor’s degrees earned by Black students in the US. They also supply more Black applicants to medical schools than non-HBCUs, and have graduated 40 percent of all Black engineers; 40 percent of all Black US Congressmembers; 50 percent of all Black lawyers; 80 percent of all Black judges; and, well, 100 percent of Black US vice-presidents. | | HBCUs have been in the spotlight over the past year, spurred by the ascension of many HBCU alumni to prominent political positions, as well as by the ongoing movement for racial equity in the US following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others. HBCUs have received donations from philanthropists and large corporations looking to support diversity and inclusion, and are viewed increasingly as sources of talent. | | If this attention and funding were sustained, HBCUs could continue to propel advancement for Black Americans—and in turn create a stronger economic performance for the US. But HBCUs are underfunded when compared with predominantly White peer institutions, with endowments seven times smaller on average than those of non-HBCUs. And HBCUs’ endowment gap is growing: it went from more than $100 million on average in 2010 to more than $220 million in 2018, McKinsey data show. | | The potential is there: HBCUs could produce even more high-earning Black graduates and develop even more Black entrepreneurs, and also decrease Black student debt and remove barriers for Black consumers. McKinsey research shows that significant economic and human value can be gained when Black Americans are fully engaged in the economy. HBCUs are perfectly positioned to foster such engagement—and to continue the crucial work they’ve been doing for almost 200 years: dramatically improving the lives and livelihoods of Black Americans. | | — Justine Jablonska, editor, New York | | |  | | OFF THE CHARTS | | Bridging the transport gap | | In a recent 25-city report, McKinsey tracked how satisfied residents are with their transport systems. While most respondents appear to appreciate the hard work urban authorities have put into transport projects, the survey showed that many urban dwellers are cranky about their options. For example, even though Seoul stands out as a leader in public-transport affordability based on objective metrics, its residents remain dissatisfied. | | | | |  | | | | PODCAST | | Foodpanda’s food for thought | | Does anyone remember the days when they couldn’t order food online? In this episode of The Venture podcast, Jakob Angele, CEO of foodpanda APAC, the Asia–Pacific business of foodpanda, reflects on building a business based on delivering restaurant meals to people’s homes. At the time of foodpanda’s founding almost a decade ago, that idea was hard to swallow for consumers and restaurants alike. Angele talks about his journey, from the days of knocking on restaurant doors to growing foodpanda into a multibillion-dollar business. | | |  | | MORE ON MCKINSEY.COM | | Practice makes perfect? | Curiosity and a desire to keep growing are what drive most of us to learn something new. Turning that desire into new capabilities, though, requires a plan. Here’s an effective strategy to continually learn, grow, and achieve development goals. | | Beyond income: Redrawing the Asian consumer map | Asia’s consumer markets are growing rapidly, as well as diversifying and segmenting. Three changes in perspective are key to understanding new consumption paths in the region. | | COVID-19: A comparison with other public-health burdens | COVID-19 is no longer the leading cause of death in some countries, which means they need to decide whether, when, and how to shift from viewing the virus as a special threat to managing it as an endemic disease. | | | | | | | FOUR QUESTIONS FOR | | Parag Khanna | | In his new book, Move: The Forces Uprooting Us, Parag Khanna, the founder of FutureMap, delves into the powerful global forces that will cause billions of people to relocate over the next decades. This is a condensed version of a recent McKinsey Author Talks discussion. | | | | | | Why is this topic relevant now, amid a pandemic with very little movement? | | Move is a book about how humanity responds to complexity. We’re facing simultaneous global risks and challenges, such as geopolitical competition, demographic imbalances, political upheaval, economic dislocation, technological disruption, and climate change—all at the same time. | | These are not parallel phenomena. In fact, they’re converging, and they’re even colliding. I’ve chosen to take this COVID-19 moment, this great lockdown, as a point of departure to look into the next ten, 20, or 30 years, to what I think of as the next great migrations. What will be our future human geography? How will the eight or nine billion of us distribute ourselves around the world? And where will be the thriving societies that overcome today’s volatility? | | Wasn’t the internet supposed to make physical mobility less relevant? | | The relationship between technology and mobility varies significantly depending on geography. So, for example, in the United States or Canada or the UK or France, a professional class can speak about working from anywhere and potentially shifting to the suburbs or becoming digital nomads. But that’s not the case for the majority of the world’s population. In Asian countries, even with fast mobile broadband, people would still push into cities for higher wages, better education, access to services, and a better quality of life. | | We have several key trends unfolding at the same time. The percentage of what are called location-agnostic workers is rising rapidly to an estimated 40 percent—and even beyond—of the global workforce. And we have geographies that are proving either more or less capable of coping with disruptions like climate change. We also have countries waking up to the need to vigorously compete in this global war for talent. So it’s the intersection of these forces and trends that will determine what destinations skilled youth are going to flock toward in the years ahead. | | Can we enforce global moral obligations in a nationalistic world? | | We do live in a nationalistic world, but ages of nationalism have overlapped with ages of mass migrations before: much of the 19th century was precisely like this. And there’s often a material interest in fulfilling moral obligations, and this would fortunately be one such case. We have a finite world population of high inequality. If we want to expand markets and achieve market scale, we need to bring technologies to people and help them become active citizens, consumers, and participants in various marketplaces. | | There is a clear self-interest in moving people to resources, and technologies to people, but we’re not going to get to this new equilibrium if we’re still governed by antiquated concepts such as sovereignty. The bottom line is that supply and demand should always dictate migration policy, and it should be colorblind. | | What surprised you when researching this book? | | I’m looking at the world population of today and trying to forecast where it will be tomorrow. In doing so, I needed to look at the new directional vectors of talent. And one of the things that caught me off guard was the rate of growth of Asian populations in western Europe, excluding the UK. There are presently only four million of what I call Asian Europeans versus 25 million Asian Americans. | | I predict that in the coming ten or 20 years, there will be more Asian Europeans than Asian Americans. Europe actually trades more now with Asia than it does with the United States, and it is seeking free-trade agreements with Asian regions like Southeast Asia and with India. Overall, Europe could prove to be more attractive in the long run to Asian talent. | | — Edited by Barbara Tierney, senior editor, New York | | | | | BACKTALK | | Have feedback or other ideas? We’d love to hear from you. | |  | | | Did you enjoy this newsletter? Forward it to colleagues and friends so they can subscribe too.

Was this issue forwarded to you? Sign up for it and sample our 40+ other free email subscriptions here. | | | This email contains information about McKinsey’s research, insights, services, or events. By opening our emails or clicking on links, you agree to our use of cookies and web tracking technology. For more information on how we use and protect your information, please review our privacy policy. | | You received this email because you subscribed to The Shortlist newsletter. | | | | Copyright © 2021 | McKinsey & Company, 3 World Trade Center, 175 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10007 | | | |